Fratelli Branca Distillery Tour, Part 1

Back in April (when still living in Italy), wife Nat and I took the road north from our Italian pre-tirement home, driving up to Milan so we could make a visit to the Fratelli Branca Distillerie, where Fernet Branca and many other delicious drinkables are made. When we showed up in the morning for our tour, we weren’t sure at all what to expect—a little talking, a little walking around the building, we just didn’t know. But it ended up being an amazing day, where we learned a ton and had some fun (huge props to Laura Baddish for helping to set it up, too). Once past the guards (serious liqueurs always need guards at the gates, cause secret formulas are too tempting to weaker minded individuals), we were met by three swell Italian folks: Elisa, Marco, and Valeria. Marco gave most of the tour, with tons of expert translating (his English is better than our Italian, but not by enough to carry on in-depth conversations) and more touring by Elisa, with Valeria filling in the cracks.

Back in April (when still living in Italy), wife Nat and I took the road north from our Italian pre-tirement home, driving up to Milan so we could make a visit to the Fratelli Branca Distillerie, where Fernet Branca and many other delicious drinkables are made. When we showed up in the morning for our tour, we weren’t sure at all what to expect—a little talking, a little walking around the building, we just didn’t know. But it ended up being an amazing day, where we learned a ton and had some fun (huge props to Laura Baddish for helping to set it up, too). Once past the guards (serious liqueurs always need guards at the gates, cause secret formulas are too tempting to weaker minded individuals), we were met by three swell Italian folks: Elisa, Marco, and Valeria. Marco gave most of the tour, with tons of expert translating (his English is better than our Italian, but not by enough to carry on in-depth conversations) and more touring by Elisa, with Valeria filling in the cracks.

The tour started in the Collezione Branca, which is a museum created by the Branca family, a museum in the distillery (the aromas of Fernet Branca and other drinks waft up as you wander the museum), collecting Branca historical items, memorabilia, and more. It really serves as a tangible history of the company in many ways, and was full of intriguing artifacts. Right at the beginning are portraits of those family members who were there at the beginning, with a picture of Bernardino Branca in the middle:

Bernardino was the original creator of the famous Fernet Branca, developing the formula with Dr. Fernet, a Swedish doctor, to assist malaria and cholera patients. With this aim, it was first tested in hospitals (where it was shown to help patients) and first sold in local farmacias, or pharmacies (quick aside: Italian pharmacists have a lot more leeway than those here in the States, in prescribing and diagnosing). The first cask that Bernardino made this herbal health mixture in is also in the museum, and lives right under his portrait:

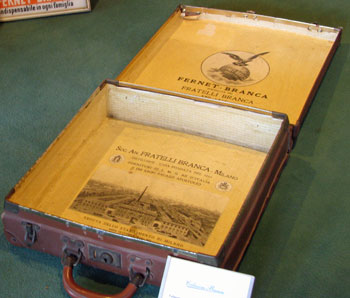

When walking through the museum, we learned more about the Branca family, which still runs the company today (the head of the company, Count Niccolo Branca, is the 5th generation of the family to make Fernet Branca). The family focus isn’t just with the Brancas, either, as our tour guide Marco is the 4th generation of his family to work at Branca (he’s been there since 1972). This lengthy dedication and devotion is quite remarkable, and shows in the end results: the liqueurs. There are lots more interesting family stories, such as those about Maria Scala, who married the third son of Bernardino and eventually became one of the first women in charge of a large company, and who originally developed the focus on continually creative Branca advertising—the company has always been on the forefront of advertising and advertising trends. One of my favorite, and a somewhat obscure, piece of marketing is this Branca suitcase:

I would carry one of those in an instant (if you have one you’re tired of, please let me take it off your hands). The museum also has loads of production implements from the past, and some that were used in the past but are still utilized today, which points towards the Branca philosophy of novare serbando, or renew but conserve. For one example, Marco showed us these giant iron pots for herb maceration and heating, which are still used today, though the stirring is done mechanically instead of by hand:

The pots were at one point stirred with both iron and wood stirrers (depending on the spices), and as the iron sticks were “cleaning” the pots, many thought that Fer-net came from some rendition of “clean iron.” Which is, I have to say, a great story. Fernet Branca gets its signature bitter, herbal, rich taste from an wide assortment of herbs, roots, spices, and other ingredients, and there’s a giant, mind-blowing, round table in the museum where you can see the complete layout of ingredients:

I knew (hey, I’ve done a little research before) that there were around 40 ingredients, and that the list included such far-reaching items as gentian root, rhubarb, myrrh, cinchona bark, galanga, saffron, and others, but I learned while there that all the products used are completely natural, and that all the suppliers have to sign a code of sorts, that says the products were obtained in a non-exploitive way. Another (and this was fascinating to me, but hey, I’m interested in odd things) fact I learned is that the real secret in the secret recipe for Fernet-Branca is how the ingredients are treated in production. Only the family knows, and the Count himself still does the treating (which means he has to go to the other distillery, in Argentina, regularly). Cool, isn’t it? After spices, we got to see tons of hip old Fernet-Branca ads, including the first one to use the eagle-over-the-world logo:

This logo was created in 1895, due to the large amount of Fernet Branca imitations being shuffled out of back alleys—always look for the eagle bringing the Branca over the world to ensure you get the real thing. There are a number of side rooms along the museum’s main path, where you can get a better picture of how Branca workers worked back in the day (as they say), with an herbalist’s room, chemist’s room:

and more. The museum is persistent in remembering not just what was made, but those who made it—not to mention that the museum itself was built by current workers at the plant. Again, there’s that whole atmosphere of devotion to people and product, to stories and to history. After looking over the production process, the spices, and hearing about the history contained within, we walked into a room full of bottles, whole tables of old Fernet Branca bottles, and bottles of other products brought out by the company, including older bottles of Branca Menta (a minty-er and sweeter version of Fernet Branca released in 1965), bottles of Carpano Antica (Branca bought the Carpano company years ago in a particularly astute moment—Carpano Antica being the first Italian vermouth, and one still made partially by hand, and the Carpano company also making Italian vermouth Punt e’ Mes), and more bottles. There’s even a whole cabinet of Fernet Branca impersonators (I suppose success always leads to imitation):

Then we stopped in the bar room (of course the museum was going to have a bar at some point), talked a bit more about advertising, had some Carpano Antica (which I loved even before stopping, and which I was happy to have a glass of even at 11:30 AM), and saw a host of happening ads for the non-Fernet-Branca-Branca brands. If the tour ended now, I would have been more than happy–but we still had the actual distillery to see! Which I’ll talk more about in Part 2, so come on back. Oh, first, check out this sweet and colorful Punt e’ Mes ad (one of about, say, 96, that I wished I had on my walls at home):

Bob Deck said:

I have an unopened bottle of Fernet-Branca that I’m trying to find out how old it is. It came from my grandpas bar when he died and looks to be very, very old. Part of the bottle is in italian and part in english. Any way to find out what year this unopened bottle is? Thank you. Bob Deck

ajrathbun said:

Hello Bob-

That bottle sounds amazing. I’m not sure the best way to date it, but you could try just taking a few photos and sending them to the folks at Branca (I’m guessing there’s a Contact Us on their site). They were all really swell people, and seemed very attuned and interested in historical Branca-ness. I’d say that might be your best bet. Another would be to upload a photo to a cocktail message board (I believe there are some on the Drink Boy site) and see if anyone has any ideas.

Good luck! Cheers-

A.J.