February 13, 2012

I’ve talked a bit about English detective-y writer Peter Lovesey in a past Cocktail Talk post, so I’ll gloss over the backstory mostly here (if you need more, head back in time), and just remind you, dear reader, that Mr. Lovesey is best known for two characters, heavyweight-but-huggable modern police detective Peter Diamond and under-appreciated Victorian police detective Sergant Cribb. The book I’m quoting today, Mad Hatter’s Holiday, features the latter and both has a good crime story and impeccable period details. A worthy read. And the below is a worthy quote, especially because I understand how sometimes a night “of gin and song” isn’t planned and then does, indubitably, take its toll.

I’ve talked a bit about English detective-y writer Peter Lovesey in a past Cocktail Talk post, so I’ll gloss over the backstory mostly here (if you need more, head back in time), and just remind you, dear reader, that Mr. Lovesey is best known for two characters, heavyweight-but-huggable modern police detective Peter Diamond and under-appreciated Victorian police detective Sergant Cribb. The book I’m quoting today, Mad Hatter’s Holiday, features the latter and both has a good crime story and impeccable period details. A worthy read. And the below is a worthy quote, especially because I understand how sometimes a night “of gin and song” isn’t planned and then does, indubitably, take its toll.

Saturday night at the Canterbury was about to take its toll. He had not planned his night of gin and song. A visit to the Canterbury was not indelibly inspired in his social diary, like evenings at the dome and the Theatre Royal.

—Peter Lovesey, Mad Hatter’s Holiday

February 6, 2012

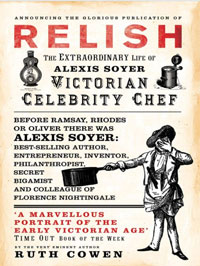

Okay, I feel I’ve extended Alexis Soyer week long enough (though I didn’t even get to the fountain in his Universal Symposium where a living Ondine frolicked among jets of curaçao, maraschino, and liqueur d’ amour), even though this sadly-not-as-well-known-as-he-should-be chef, bon vivant, celebrity, inventor, and philanthropist deserves much more. You’ll just need to get out there and read Relish by Ruth Cowen and then help me spread the Soyer mythology around. Most of the quotes from the book that I’ve reproduced here have a drinky angle, as you might expect on a blog called Spiked Punch. But for this final quote, I wanted to dish up a tasty food number, and have decided on a quote that details one of his famous menus from his days as head of the Reform Club’s kitchen. It seemed a fitting end, as Soyer definitely like the big productions. This one was a dinner in honor of Imbrahim Pasha, the regent of Egypt.

Okay, I feel I’ve extended Alexis Soyer week long enough (though I didn’t even get to the fountain in his Universal Symposium where a living Ondine frolicked among jets of curaçao, maraschino, and liqueur d’ amour), even though this sadly-not-as-well-known-as-he-should-be chef, bon vivant, celebrity, inventor, and philanthropist deserves much more. You’ll just need to get out there and read Relish by Ruth Cowen and then help me spread the Soyer mythology around. Most of the quotes from the book that I’ve reproduced here have a drinky angle, as you might expect on a blog called Spiked Punch. But for this final quote, I wanted to dish up a tasty food number, and have decided on a quote that details one of his famous menus from his days as head of the Reform Club’s kitchen. It seemed a fitting end, as Soyer definitely like the big productions. This one was a dinner in honor of Imbrahim Pasha, the regent of Egypt.

The meal began, according to custom, with a selection of exquisite soups–considered by all epicures to be the essential health-giving aperitifs of any great dinner. They included consommés such as Potage à la Victoria, a delicate veal broth garnished with blanched cockscombs; Potage à la Colbert, a vegetable soup flavored by glazed Jerusalem artichokes laboriously cut into pea-sized balls, and Potage à la Comte de Paris, a sherry-colored, intensely flavoured meat soup filled with macaroni ribbons and delicate chicken quenelles. As the tureens were cleared, and as the noise levels rose to compete with the band, the members moved on to the most delicate dishes, the hot fish. Turbot à la Mazarin, light poached and served with a delicately beautiful pink cream sauce made with butter and lobster roes; pan-fried trout in a sherry sauce; a pyramid of whitings, deep friend and served à la Egyptienne in tribute to the guest of honor, and wild salmon from the river Severin–which Alexis considered the very best–line caught that morning and brought in on the afternoon train, to be pounced on by the kitchen staff and immediately scraped, gutted, washed, and prepared in a simple cream gratin. Then came the dishes for the main service, carefully arranged on the crisp white damask cloths–two, four, or six platters of each item laid out in perfect symmetry. These included a choice of róts, such as young, tender turkeys, no bigger than chickens, their necks skinned but heads left intact, tucked under their wings. There were also hares in a red-currant sauce, capons with watercress, plump white ducklings, spit-roasted and served with the juice of sour bigarade oranges. The first relevés were also waiting: an almighty baron of beef; haunches of mutton roasted à la Soyer and saddle of lamb à la Sévigné, served with veal quenelles, stewed cucumbers, and asparagus puree. There were also more elaborate removes, such as Chapons à la Nelson, a complex dish which involved gluing truffle- and mushroom-stuffed capons into pastry croustades shaped like the prow of a ship–complete with sails, portholes, and anchor–and fixing them into waves of mashed potatoes. Soyer adored these elaborate culinary trompes l’oeil, and at the same banquet produced for the first time his Poulardes en Diadem, this the time pastry croustade resembling a jeweled crown, stuffed with roasted chickens, boiled ox tongues, and glazed sweetbreads. He adorned them with attelettes–another Soyer innovation–newly commissioned gold and silver skewers with carved tops representing fantastical animals, birds, shells, and knight helmets. The attelettes, or hatelets as the popular electroplated copies were called, were the equivalents of culinary jewelry, and would be strung with crawfish, truffles, and quenelles before being stuck into the dish as the ultimate sparkling garnish.

Okay, that’s only about half of this dinner. But what a half! To get the full menu (and to read the full story of Soyer), pick up or download Relish. And give a toast to Soyer!

PS: Missed the other Soyer Cocktail Talks? Read up on Soyer Cocktail Talk I, Soyer Cocktail Talk II, and Soyer Cocktail Talk III.

February 3, 2012

I’m going to skip the preamble for this post (you can catch that in Alexis Soyer Cocktail Talk I and Alexis Soyer Cocktail Talk II) and get right the quotes, which are again taken from the superb Soyer bio Relish by Ruth Cowen. These quotes are again showing why Soyer fits on a cocktail and drinks blog (even though he’d probably be more associated with the culinary arts as opposed to the cocktail arts. Though really, they go together so nicely). And the first one uses the phrase “oesophagus burners,” which is a phrase I’d like to see back in circulation.

I’m going to skip the preamble for this post (you can catch that in Alexis Soyer Cocktail Talk I and Alexis Soyer Cocktail Talk II) and get right the quotes, which are again taken from the superb Soyer bio Relish by Ruth Cowen. These quotes are again showing why Soyer fits on a cocktail and drinks blog (even though he’d probably be more associated with the culinary arts as opposed to the cocktail arts. Though really, they go together so nicely). And the first one uses the phrase “oesophagus burners,” which is a phrase I’d like to see back in circulation.

Beneath this terrace, reached via a wooden staircase, was an American-style bar called The Washington Refreshment Room, which was to all intents and purposes the first cocktail bar in London. It provided thirsty customers with such daring modern concoctions as ‘flashes of lightning, tongue twisters, oesophagus burners, knockemdowns, squeezemtights . . . brandy pawnees, shadygaffs, mint juleps, hailstorms, Soyer’s Nectar cobblers, brandy smash, and hoc genus omne.’ More than forty cocktails were on offer, and among the candidates for the job of barmen, said Sala, was ‘an eccentric American genius, who declared himself perfectly capable of compounding four at a time, swallowing a flash of lightning, smoking a cigar, singing Yankee Doodle, washing up the glasses, and performing the overture to the Huguenots on the banjo simultaneously.

. . . the festivities almost came to a dramatic end when a paper lantern caught fire and the flames quickly spread across the roof–but a young officer hoisted himself up to the beams and managed to extinguish it. The band resumed, and Alexis produced his special punch–Crimean Cup à la Marmora–a lethal blend of iced Champagne, Cognac, Jamaican rum, maraschino, orgeat syrup, soda water, sugar, and lemons.

Tags: Alexis Soyer, Champagne, Cognac, Crimean Cup à la Marmora, punch, Relish, Rum

Posted in: Alexis Soyer, Champagne & Sparkling Wine, Cocktail Talk, Cognac, Punch, Rum

February 1, 2012

In our first Alexis Soyer Cocktail Talk post, I talked more about the celebrated (though not celebrated enough today) celebrity chef, bon vivant, and charitable Frenchman who lived in London in the mid-1800s. And about the worthy and needed biography of him by Ruth Cowen, called Relish, which I just read and liked lots. The following quotes are from said book, as are those in the other Soyer posts, in hopes that I can spread the Soyer legend around (as well as convince you to search out more about him). Here are more quotes to give you any idea of Soyer, starting with two about Soyer’s Nectar, a branded drink he came up with that was a bubbly-lemon-cinnamon mix that happened to be blue–he was a bit colorful, after all.

In our first Alexis Soyer Cocktail Talk post, I talked more about the celebrated (though not celebrated enough today) celebrity chef, bon vivant, and charitable Frenchman who lived in London in the mid-1800s. And about the worthy and needed biography of him by Ruth Cowen, called Relish, which I just read and liked lots. The following quotes are from said book, as are those in the other Soyer posts, in hopes that I can spread the Soyer legend around (as well as convince you to search out more about him). Here are more quotes to give you any idea of Soyer, starting with two about Soyer’s Nectar, a branded drink he came up with that was a bubbly-lemon-cinnamon mix that happened to be blue–he was a bit colorful, after all.

He did not have to wait long for yet another bundle of ecstatic reviews. On 13 July The Sun declared: ‘It beats all the lemonade, orangeade, citronade, soda-water, sherry-cobbler, sherbet, Carrara-water, Seltzer, or Vichy-water we ever tasted.” The Globe dubbed Soyer the ‘Emperor of the Kitchen,’ and duly recommended the addition of a tot of rum.

The Nectar was particularly popular as a mixer, and Alexis, who with some justification could be called the pioneer of the English cocktail, published a variety of recipes for ‘Nectar Cobblers’ and other glamorous boozy compounds.

Cowen’s Soyer biography is packed with descriptions of the almost impossible to believe dinners he made, sometimes for groups by the hundreds and thousands. Whenever, going forward, I hear people talk about their decandent dinners, I’ll laugh and point them to Relish. The following quote is part of one of the more restrained meals in the book, one Soyer created for the Grand Dinner of the Royal Agricultural Society festival:

The bill of fare included–on top of a whole Baron and Saddleback of Beef à la Magna Charta–33 dishes of ribs of beef, 35 dishes of roast lamb, 99 galantines of veal, 29 dishes of ham, 69 dishes of pressed beef, two rounds of beef à la Garrick, 264 dishes of chicken, 33 raised French pies à la Soyer, 198 dishes of mayonnaise salad, 264 fruit tarts, and 198 dishes of hot potatoes. It also included 33 Exeter puddings, which Soyer had invented especially for the occasion. There were essentially an alcohol-steeped reworking of his boiled Plum Bolster, for which, in The Modern Housewife, he had applied the alternative name of ‘Spotted Dick’ for the first time in an English cookbook. They were big, rich, doughy balls of suet and sugar, to which Alexis added rum and ratafias and then smothered with a sweet, shining blackcurrant and sherry sauce.

January 30, 2012

If you’re interested in cooking, in living well, use a gas stove, have eaten while in the military, have worn a beret or enjoy wearing colorful clothes, like French, English, or other European cuisine, have a healthy (or unhealthy) interest in celebrity chefs or celebrities in general, are curious about kitchen inventions, have been known to knock back a bit of bubbly regularly, are wondering where the first American-style cocktail bar was in London, have a thing for Dickens’ era history, or just want to learn about an awfully interesting fella, I strongly suggest you read Roth Cowen’s Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef. It’s quite a rollicking read as far as biographies go, because Soyer was quite a rollicking character. A famous chef in Paris by the time he was 20 (called “The Enfant Terrible of Monmartre”), Soyer really became a hit after political uprising sent him to England (he’d made one amazing, and amazingly described, banquet for the wrong people when the right people were uprising). He eventually became head chef at the famous Reform Club, where he designed the most modern kitchen ever seen, including being one of the first to use gas stoves instead of coal, along with a bunch of other culinary-minded inventions and innovations. Eventually, he did a host of things (I’m not going to mention them all–really, read the book) consumerist and philanthropic, published cookbooks, had his name on condiments, had a hugely fantastic failure of a, well, restaurant isn’t really the word, but at least is related, made and lost lots of money, became well-known, and then died in his late 40s. For the amount of work he did for the poor and military of the U.K., you’d think he’d be better revered, but he hasn’t been (though maybe the last few years have been kinder). As you can tell, I was pretty struck by Soyer when reading the book, so much so that I’ve decided to have a week of quotes from the book (which may mean three posts, maybe more), some by him, and some about him. Starting with one from earlier in his life, and then moving on–all to try and entice you to learn more about the great Soyer.

If you’re interested in cooking, in living well, use a gas stove, have eaten while in the military, have worn a beret or enjoy wearing colorful clothes, like French, English, or other European cuisine, have a healthy (or unhealthy) interest in celebrity chefs or celebrities in general, are curious about kitchen inventions, have been known to knock back a bit of bubbly regularly, are wondering where the first American-style cocktail bar was in London, have a thing for Dickens’ era history, or just want to learn about an awfully interesting fella, I strongly suggest you read Roth Cowen’s Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef. It’s quite a rollicking read as far as biographies go, because Soyer was quite a rollicking character. A famous chef in Paris by the time he was 20 (called “The Enfant Terrible of Monmartre”), Soyer really became a hit after political uprising sent him to England (he’d made one amazing, and amazingly described, banquet for the wrong people when the right people were uprising). He eventually became head chef at the famous Reform Club, where he designed the most modern kitchen ever seen, including being one of the first to use gas stoves instead of coal, along with a bunch of other culinary-minded inventions and innovations. Eventually, he did a host of things (I’m not going to mention them all–really, read the book) consumerist and philanthropic, published cookbooks, had his name on condiments, had a hugely fantastic failure of a, well, restaurant isn’t really the word, but at least is related, made and lost lots of money, became well-known, and then died in his late 40s. For the amount of work he did for the poor and military of the U.K., you’d think he’d be better revered, but he hasn’t been (though maybe the last few years have been kinder). As you can tell, I was pretty struck by Soyer when reading the book, so much so that I’ve decided to have a week of quotes from the book (which may mean three posts, maybe more), some by him, and some about him. Starting with one from earlier in his life, and then moving on–all to try and entice you to learn more about the great Soyer.

…he was particularly skilled at mimicking the comic turns of whichever show was playing. He had a musical ear and sang, by all accounts, nearly as well as Levasseur, one of the most admired bass singers in France. A dandy with a penchant for outlandish costumes, a terrible flirt, a skiller storyteller and an impish practical joker, Alexis had even considered switching careers to try his luck on the stage.

By two in the morning he would be at the Provence Hotel, the Ceder Cellars, or Evan’s Late Supper Rooms in Covent Garden–also frequented by Thackeray–where customers descended a flight of stone steps to a smoky basement called the Cave of Harmony, which was in fact a large raucous music hall and café serving simple, alcohol-absorbing meals of fatty chops, sausages, grilled kidneys in gravy, Welsh rarebit, and baked potatoes. Here the exclusively male clientele would stay until the early hours, cheering and heckling the professional glee singers and comic acts while knocking back the cheap booze–stout, pale ale, punch, grog, hot whisky and water.

January 23, 2012

As the political, um, talk is reaching its election-year-in-January proportions (talk which I’m sure by the actual election will reach astronomical asinine-ness), I thought I’d throw in a Cocktail Talk quote from Graham Greene. It’s not, however, specifically about politics, but it seems relevant. It’s not, either, from one of my favorite books by Mr. Greene (who is of course super-fan-tabulous), but from a perhaps lesser novel called Travels with My Aunt. The fact that it’s one of his books makes it better than most books on the top seller list, however. But, to get back to politics. And booze. The reason this quote seems so perfect for an election year goes back to a thought I once had (and if anyone says “the one thought you ever had,” well, good point), that if we could see those fight’n politicians after a few glasses of bubbly we could probably find out more about them then listening to any ol’ debate. Which leads to this quote, which I might use as a slogan if I ever run for office:

As the political, um, talk is reaching its election-year-in-January proportions (talk which I’m sure by the actual election will reach astronomical asinine-ness), I thought I’d throw in a Cocktail Talk quote from Graham Greene. It’s not, however, specifically about politics, but it seems relevant. It’s not, either, from one of my favorite books by Mr. Greene (who is of course super-fan-tabulous), but from a perhaps lesser novel called Travels with My Aunt. The fact that it’s one of his books makes it better than most books on the top seller list, however. But, to get back to politics. And booze. The reason this quote seems so perfect for an election year goes back to a thought I once had (and if anyone says “the one thought you ever had,” well, good point), that if we could see those fight’n politicians after a few glasses of bubbly we could probably find out more about them then listening to any ol’ debate. Which leads to this quote, which I might use as a slogan if I ever run for office:

Champagne, if you are seeking the truth, is better than a lie detector.

–Graham Greene, Travels with My Aunt

January 11, 2012

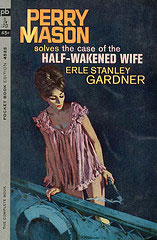

As I mentioned once in a Cocktail Talk post over two years ago (amazing that I’ve been writing this blog for so long, now that I mention it), I’m not a huge Perry Mason book fan, meaning those (and there were tons) written by Erle Stanley Gardner. I am a gigantic Perry Mason television show fan, however. Which points I suppose to how wacky I am, or some such. But the books just seem a tad too smart about themselves, while the show seems just the right pitch of genius and atmosphere. However, I do still pick up the occasional Perry Mason book, mostly because many of the original pocket book covers are joys to behold. Take the one pictured here–lovely lady, in negligee, with smoking pistol, on a boat. Gawd, that’s wonderful. And this book I liked more than others, too, as it seemed a little less in hand at times to me, and had the full contingent of Perry Mason favorites: dashing detective Paul Drake, saucy and swell secretary Della Street, and cuddly losers (at least when facing Perry) Lieutenant Tragg and DA Hamilton Burger. And, the following little gem of an exchange:

As I mentioned once in a Cocktail Talk post over two years ago (amazing that I’ve been writing this blog for so long, now that I mention it), I’m not a huge Perry Mason book fan, meaning those (and there were tons) written by Erle Stanley Gardner. I am a gigantic Perry Mason television show fan, however. Which points I suppose to how wacky I am, or some such. But the books just seem a tad too smart about themselves, while the show seems just the right pitch of genius and atmosphere. However, I do still pick up the occasional Perry Mason book, mostly because many of the original pocket book covers are joys to behold. Take the one pictured here–lovely lady, in negligee, with smoking pistol, on a boat. Gawd, that’s wonderful. And this book I liked more than others, too, as it seemed a little less in hand at times to me, and had the full contingent of Perry Mason favorites: dashing detective Paul Drake, saucy and swell secretary Della Street, and cuddly losers (at least when facing Perry) Lieutenant Tragg and DA Hamilton Burger. And, the following little gem of an exchange:

Drake said, “Here’s a car with three of my operatives now. What do we do first?”

“Put them out the way I said, so they can watch the apartment, the garage, and the windows.”

“Okay, then what?”

“Then,” Della Street interposed with firm determination,“we get a cup of hot coffee and it there’s any brandy in the car, we spike it with brandy. My chattering teeth are chipping off.”

“That,” Mason agreed, “is an idea.”

–Erle Stanley Gardner, The Case of the Half-Wakened Wife

January 8, 2012

In an earlier Cocktail Talk post, I had a quote from Qiu Xiaolong’s book Death of a Red Heroine (which I highly recommended then and still do now), and talked a bit about the author and his main character in the series, Shanghai poet and Chief Inspector Chen (though Chen’s second-in-command Detective Yu gets a lot of deserved face time on the page, too, with chapters often switching off with the two as alternating protagonists). So, for more background, go read that post. Cause here I just want to get straight into this quote, which is from a book in the series called A Case of Two Cities, which takes place not only in late 20th century Shanghai but also Los Angeles and St. Louis. This quote is actually Chen remembering “a short poem by Wang Han, an eighth-century Tang dynasty poet,” and would have made a dandy addition to In Their Cups: An Anthology of Poems About Drinking Places, Drinkers, and Drinks had I known of it.

In an earlier Cocktail Talk post, I had a quote from Qiu Xiaolong’s book Death of a Red Heroine (which I highly recommended then and still do now), and talked a bit about the author and his main character in the series, Shanghai poet and Chief Inspector Chen (though Chen’s second-in-command Detective Yu gets a lot of deserved face time on the page, too, with chapters often switching off with the two as alternating protagonists). So, for more background, go read that post. Cause here I just want to get straight into this quote, which is from a book in the series called A Case of Two Cities, which takes place not only in late 20th century Shanghai but also Los Angeles and St. Louis. This quote is actually Chen remembering “a short poem by Wang Han, an eighth-century Tang dynasty poet,” and would have made a dandy addition to In Their Cups: An Anthology of Poems About Drinking Places, Drinkers, and Drinks had I known of it.

Oh the mellow wine shimmering

in the luminous stone cup!

I am going to drink

on the horse

when the army Pipa starts

urging me to charge out.

Oh, do not laugh

if I fall dead

drink in the battlefield.

How many soldiers

have really come back home

since time immemorial?

–Wang Han, quoted in Qiu Xiaolong’s A Case of Two Cities

I’ve talked a bit about English detective-y writer Peter Lovesey in a past Cocktail Talk post, so I’ll gloss over the backstory mostly here (if you need more, head back in time), and just remind you, dear reader, that Mr. Lovesey is best known for two characters, heavyweight-but-huggable modern police detective Peter Diamond and under-appreciated Victorian police detective Sergant Cribb. The book I’m quoting today, Mad Hatter’s Holiday, features the latter and both has a good crime story and impeccable period details. A worthy read. And the below is a worthy quote, especially because I understand how sometimes a night “of gin and song” isn’t planned and then does, indubitably, take its toll.

I’ve talked a bit about English detective-y writer Peter Lovesey in a past Cocktail Talk post, so I’ll gloss over the backstory mostly here (if you need more, head back in time), and just remind you, dear reader, that Mr. Lovesey is best known for two characters, heavyweight-but-huggable modern police detective Peter Diamond and under-appreciated Victorian police detective Sergant Cribb. The book I’m quoting today, Mad Hatter’s Holiday, features the latter and both has a good crime story and impeccable period details. A worthy read. And the below is a worthy quote, especially because I understand how sometimes a night “of gin and song” isn’t planned and then does, indubitably, take its toll.